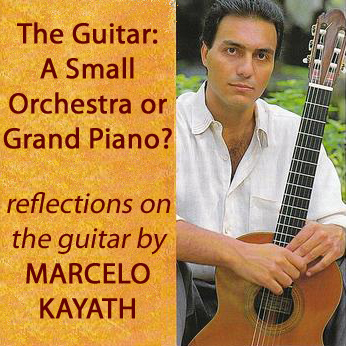

"Reflections On The Guitar" by Marcelo Kayath

Here’s an article written by Marcelo Kayath, who in the early 80’s was considered one of the great up-and-coming guitarists of his generation. I find his thoughts on the current state of the guitar really interesting, but I have a feeling that not everyone will agree with him. I’m very curious to see what everyone has to say.

GUITAR – A SMALL ORCHESTRA OR A GRAND PIANO?

*Disclaimer – Please read first: The text below is merely my personal opinion. My intention is simply to open up debate and prompt a collective reflection on points that are critical to me: our conception of the instrument and the way in which we view music and recent trends in relation to the guitar. I hope the points below serve as a starting point for a constructive and fruitful debate for all. – Marcelo Kayath

THE BEGINNING: FROM SOR/GIULIANI TO TARREGA

We could choose any starting point for our debate, but I find it interesting to start at the end of the 18th century, when the modern guitar was in its early stages and repertoires were beginning to take form. Unfortunately, in this golden age of music, the guitar did not appeal to Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn or Schubert. Instead, we have Sor, Giuliani, Aguado, Carulli and other lesser-known musicians. They were extraordinary musicians and outstanding players, but they were not in the same league as the greatest geniuses of music history. Since there’s no use in trying to change the past, let’s stick to what we have, which luckily is quite a lot.

Even in this initial phase, the issue of the sound of the guitar was already becoming evident. The commentary at the time about Sor’s small recitals was that he had interesting pieces and a great deal of musicality, but that the sound was too dull, typical of those – like Sor – who played without nails. Technically speaking, Giuliani and Aguado were considered the virtuosi, and Sor was held out as the most musical. But despite Aguado and Giuliani’s virtuosity, and Sor’s musicality, the guitar was reserved for salon music, with hardly any use in more “serious” environments. One of the main problems was the instrument’s own sound limitation, since the guitars of the day were a far cry from the projection and volume of the sound of modern guitars. Furthermore, the strings available at the time were much less reliable than modern strings, and it was often challenging for a musician to stay in tune while playing.

In the 19th century, the instrument saw remarkable technical development, as a revolutionary conception of a new guitar was proposed by Antônio de Torres in his workshop in Seville. Other virtuosi – such as Julian Arcas and, shortly thereafter, Francisco Tarrega – also appeared. The modern repertoire began to take shape with the original works of Tarrega and the first transcriptions of Bach, Albeniz, Granados and many others.

Despite this technical development, the debate on the use of nails remained intense at that time. Despite his great musicality and virtuosity, Tarrega played with a “muffled” sound, without nails, hindering his acceptance in a large concert hall. The discouraging panorama prevailed throughout the 19th century, with the guitar relegated to the drawing room, without much technical musical interest.

SEGOVIA: THE GREAT LEAP FORWARD

Despite the dismal outlook, by the outset of the 20th century the seeds of the modern guitar had been sown. There was already a repertoire of classics from the 19th century (Sor, Giuliani, etc.), original compositions (Tarrega and other Spaniards), and a few transcriptions of Tarrega and his disciple Miguel Llobet. Many Spanish luthiers such as Manuel Ramirez and Francisco Simplicio began to build good instruments in the style of Torres. With this backdrop, Andrés Segovia arises. With the death of Tarrega in 1909 (young Segovia appears in a historical photograph near the coffin), Segovia begins his long trajectory, encouraged by Llobet and others.

Segovia quickly realizes the limitations of the career he has chosen: the repertoire was small and the sound of the guitars was insufficient for a large concert hall. And, worse, there was no respect for the instrument. In Spain at the beginning of the century, the guitar was a thing of the flamencos in the streets and bars, a remarkably similar picture to the circles of streetwise “choro” musicians common in the Lapa neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro at the time. It was unthinkable in that environment for the guitar to be considered a serious concert instrument like the violin or the piano. Segovia was continuously advised to change instruments, since he was supposedly “wasting time” by dedicating himself with such zeal to such a demoralized instrument.

What did Segovia do? With great intelligence and vision, he launched the pillars of the modern guitar, seeking to put the guitar on the same level as other instruments. Throughout his life, Segovia never deviated from certain basic principles:

- Original repertory: In the absence of works of great classical composers, Segovia encouraged new composers to write pieces for the instrument. From this effort arose Ponce, Tedesco, Torroba, Villa-Lobos and many others. It is important to remember that the most famous works that we know of are only the visible tip of the iceberg. There are hundreds of “lost” pieces in Segovia’s library in Madrid that were written for Segovia by dozens of composers and discarded by him. Despite Angelo Gilardino’s marvelous work as curator of the Segovia library in reviving some of these lost pieces, the majority, with few exceptions, are less interesting musical pieces. But the fact is that Segovia needed a repertoire to be able to give concerts and have a professional career, and so this initial gap was bridged.

- First-rate instruments: As early as 1912, Segovia acquired the famous Manuel Ramirez that is now displayed in a museum in New York. Throughout his life, Segovia always searched for guitars that allowed him an outlet for his musical ideas, not just an instrument that he could use to play loud and fast. The main luthiers chosen were Hauser, Fleta, and Ramirez. It is worthwhile to note that Segovia played several Hausers over the years, always looking for something more, until establishing himself with the famous Hauser of 1937 that was his travel companion for over 20 years.

- Quality transcriptions: Segovia had a basic premise: to transcribe only pieces that would sound better on the guitar than on the original instrument. We can take issue with many transcriptions of doubtful taste to our contemporary ears, but we have to acknowledge that within the Segovian conception they were a coherent part of a whole. Segovia often said that one of the happiest days of his life was when he was given as a present that German book of pieces for lute by Bach, thus enabling the first transcriptions of pieces of suites for lute.

- Sound: Segovia always sought a beautiful sound, perfect plucking and vibrato. For him, music meant beautiful sound. Even among the main disciples of Segovia one notes a constant concern with the production of a sweet, velvety sound. Audiences around the world, although unfamiliar with the guitar and its nascent repertoire, were seduced by the marvelous sound of Segovia, especially in the period in which Segovia used the famous Hauser of 1937.

- The guitar as a little orchestra: In line with a tradition that in my view started with Tarrega, Segovia always thought about colour and timbre. He believed that the guitar was not just another string instrument, but a little orchestra waiting to be unlocked. In several Segovia recordings and videos one hears metallic echoes of the brass section of the orchestra, alternating with the sweetness of the violin or the deep bass sound of the cello.

Here we could interject a polemical question: could Segovia have encouraged more “modern” composers to write for the guitar, instead of concentrating only on the Spanish and other more romantic and melodious composers? Why didn’t Segovia have Falla write us other pieces? Why didn’t he ask Stravinsky? Why did he shun Martin’s Pieces Bréves? Segovia’s conservative musical taste is frequently criticized and this may be partially true in hindsight, but in all fairness to Segovia we should remember the historical context. In the 1920s and 30s, Segovia’s struggle was to convince the musical world that the guitar merited respect. It was a struggle to have a chance, to be heard. Often times, recital opportunities were fought for tooth and nail, since the concert promoters doubted that the guitar could hold up for an entire concert and even attract the interest of the general public. In Spain at that time, there was total skepticism. Hence, recitals were high risk, on an instrument still in the initial phase of acceptance and with a repertoire of mediocre quality (in comparison to the great classics). If the concert was no good, there probably wouldn’t be a second chance. We should also remember that Segovia was building a new repertoire for him to play and that all that Segovia did, for better or for worse, was always with great conviction.

In this light, the spectacular success of Segovia, especially after the end of World War II, was a practical demonstration that the formula was working: a good repertoire and interesting transcriptions, all very well played and arranged on first-rate instruments with a wonderful sound. Segovia was helped further by the advent in the mid-1940s of nylon strings made by Albert Augustine, which enabled him to increase the projection of the instrument’s sound and perhaps for the first time in history easily tune the guitar during a concert.

THE CHANGING OF THE GUARD: BREAM/WILLIAMS AND THE 1960s and 70s

The roaring success of Segovia after the war and his innumerous LPs in the 1950s gave rise to a legion of admirers and aficionados, the most noteworthy of whom were Julian Bream and John Williams.

Julian Bream’s appearance was nothing short of spectacular. A great fan of Segovia’s, the young Bream’s initial aspiration was to study with the great master. This almost happened in the 1940s, but Segovia ended up losing interest in “adopting” Bream as a pupil, who was thus forced to develop his own technique and find his own way. Bream also had to face many barriers, starting with the fact that guitar was not taught at the Royal College of Music, which led him to study piano (at that time, he was told not to bring that “thing” in there). Despite the difficulties, Bream persevered, and the fact that he did not have Segovia as a master was ultimately a blessing in disguise.

Bream not only adopted Segovia’s formula, but also “perfected” it and enormously increased the instrument’s musical frontiers. First, he expanded the musical frontier “backward,” by intensely reliving the music of Dowland and other composers of the Elizabethan era. Second, he began to play entire suites of Bach and other baroque composers and not just select pieces of isolated suites (in addition to the first full recording of the Preludes of Villa-Lobos). Third, he expanded the repertoire “forward” by inviting contemporary composers such as Arnold, Henze, Berkeley, Walton, Tippet, Britten, and many others to write for the guitar and by fleeing from the commonplace Spanish and romantic style of the Segovia era. Fourth, by recording with ancient music ensembles, singers, harpsichordists, etc., Bream showed the public a facet of the guitar as an instrument for chamber music. Fifth, Bream made surprising transcriptions, demonstrating unimagined capabilities of the instrument, in a spectrum that ranged from Bach, Scarlatti, Diabelli, Boccherini and Cimarosa to pieces by Debussy and Ravel. It is interesting to note that Bream avoided the Segovia repertoire: to my knowledge he never recorded Ponce and recorded Tedesco only recently, on one of his last CDs for EMI.

In my opinion, after Segovia, Bream was the greatest apostle of the idea of the guitar as a small orchestra. Despite the changes in timbre and often exaggerated nuances, Bream demonstrated new possibilities in timbre and took the guitar-orchestra to a higher plane, in a clear evolution in relation to Segovia. This also reflected on his choice of instrument: like Segovia, Bream always looked for guitars that enabled him to obtain interesting musical results, even if this often meant greater technical effort.

I like to think of Bream always as the hard-working blue collar worker of the guitar, as he had to study very hard to overcome technical deficiencies and physical difficulties. I saw an interview of Bream in 1976 in which he said he had to develop his technique practically all by himself, and that it was a shame he didn’t have someone to teach him how to hold the instrument, technique, etc. In the 1970s, Bream even had to seek medical help for the muscular pain in his hands, which was when he discovered (according to him) that he had learned how to play the guitar the wrong way! In a famous video, Bream shows specific exercises he had to do with his left hand to “relearn” the guitar technique, a kind of physical therapy. An authentic exercise in humility for someone who at the time was considered by many to be the best guitarist in the world.

The case of John Williams was quite different. Taught initially by his father Len Williams and later adopted as a pupil and oriented by Segovia in his pre-teen years, Williams developed a perfect technique from an early age, playing with an ease and skill never before seen in the history of the instrument. Segovia even did something unheard of: he wrote a letter of presentation for Williams when he was to debut at Wigmore Hall in 1958, calling him the “prince of the guitar” (obviously, Segovia was still king). From the outset of his career, and still clearly under Segovia’s influence, Williams made technically impressive recordings, with records of the Spanish repertoire and a recording of Aranjuez with Ormandy. In the 1960s and 70s, Williams also began to go his own way, recording things such as Partita No. 1 by Dodgson and Concerto No. 1 by Leo Brouwer, in a clear attempt to break with Segovian tradition and to show that his musical ideas had evolved over the years. At that time, Bream/Williams were nearly a duopoly, which was later cemented by their recordings as a duo (“Together” in 1971 and “Together Again” in 1974).

Nonetheless, in contrast with the “classical British” world of Julian Bream, Williams demonstrated a more politicized artistic vein from an early age by recording a protest record with the Greek singer Maria Farandouri and making declarations questioning the Vietnam War, very much in line with his own generation in the 1960s. In addition, maybe motivated by commercial interests and the construction of a “younger” image for the guitar more in line with the 1960s, Williams formed the pop-light group called Sky, recorded with pop singer Cleo Laine and began to play sporadically in jazz clubs in London. In the 1970s, Williams also began to promote the music of Barrios.

In my opinion, Williams was the first great representative of the “grand piano” guitar. Perfect sound, strong, even-tempered, skill, velocity, clarity, etc., Williams displayed surprising technical perfection and inspired countless guitar players to seek similar perfection. I felt that irresistible urge myself as a teenager growing up in the 1970s as a huge Williams fan. But in my opinion, the musical results were more modest than those of Julian Bream. It is true that Williams has a tremendous contribution to the development of the guitar, and he certainly made several important transcriptions (Cordoba de Albeniz, Valses Poeticos by Granados, Baroque music, chamber music, just to name a few) and promoted quite a few composers (Dodgson, Barrios, Brouwer, Takemitsu and many others), but his legacy in terms of repertoire for the guitar unfortunately did not reach anything near the heights of Segovia or Bream.

In my view, the “Williams style” also reflected on his choice of instrument. After many years playing on a Fletas, as of the 1980s Williams began to use “easy-to-play” guitars with a sound that was apparently strong, but of less quality. Many guitarists made a veiled attempt to reinvent the traditional guitar, which was said to no longer meet the current needs of concert players. According to this school, it was necessary to build guitars with great volume of sound that were easy to play (speed above all else!). New guitars appeared with “revolutionary” designs from luthiers such as Humphrey, Gilbert, and Smallman.

It is noteworthy that around the same time Bream took the opposite direction. Mainly as of the 1990s, Julian Bream abandoned his traditional Romanillos and returned to his origins, beginning to record always with a Hauser I that belonged to Rose Augustine. Also around that time Bream recorded a great transcription of Lutoslawski, new pieces from Takemitsu and a new Sonata by Leo Brouwer, in his never-ending quest to expand the repertoire and the musical frontiers of the guitar. In my opinion, the divergent musical choices of Bream and Williams are highly symbolic of the differences that mark both of these great musicians.

THE 1980s AND 90s: RUSSEL AND BARRUECO

The search for technical perfection immediately carried into the following generation, as two great guitarists came onto the scene: Manuel Barrueco and David Russell. Barrueco had an explosive debut in the 1970s with two spectacular records (Villa-Lobos and Albeniz/Granados), while Russell was able to reach greater and well-deserved fame only in the early 1980s.

Although both were exceptional guitarists and had different musical temperaments (and both served as an inspiration to me in my early years), in my opinion Barrueco and Russell have in common the concept of “master” of the guitar played as a grand piano: well-tempered notes, little or no variation in timbre, perfect technique, loud volume, and always using instruments that were “easier” to play. At that time, the Bream style of nuances and timbres began to be seen as something “eccentric,” while Segovia began to be judged outside of his historic context. Based on a few off recordings of Segovia in the late 1960s and early 1970s, an entire generation of guitarists began to repudiate the Segovia’s legacy, believing that the old Segovia, with his exaggerated rubati and “imperfect” technique was an outdated Romantic outgrowth.

Despite the reissuance of CDs in the 1990s with former recordings from the 1930s by young Segovia, unfortunately this skewed vision ended up being the predominate one. As the concept of the “grand piano” guitar became more popular, growing numbers of representatives of this current became better equipped, technically, of which Ana Vidovic, with her immense talent, is the most recent example.

THE CURRENT MOMENT: CROSSROADS

If the guitar has never been played with such technical perfection, then why the relative lack of public interest in the classical guitar? In a conversation I had at my debut in London in 1985, John Duarte told me that in the sixties any guitarist would have been able to fill Wigmore Hall, such was the interest in the instrument and popularity of the repertoire. Nowadays, a guitarist will have a hard time filling an entire hall. Even John Williams, with his well-deserved immense popularity, who has always filled venues no matter where he played, now finds it slightly more difficult to fill a concert hall. Why is it that guitarists are increasingly playing only for other guitarists? Are we going back to the starting point?

A few factors have obviously affected classical music as a whole, and not just the guitar. The hyperactivity of modern life, exhaustion after coming home from work, stress (and laziness) of leaving home and going to the concert hall, and the risk of muggings, etc. are just a few of these factors. The lack of musical education at school makes it very difficult to entice a new generation of listeners, and audiences are visibly aging at classical music concerts.

The advent of the CD and the DVD has complicated the situation even more. We should remember that to hear quality sound at the time of Segovia it was necessary to go to the concert hall and hear the artist live. Today, not only is it possible to see and hear most artists with perfect sound without leaving home but entire concerts can also be seen over the Internet, or on YouTube. What’s worse, at home you can hit the pause button and grab a beer. As entire discographies are being downloaded over the Internet and recording companies have lost interest in promoting new classical artists, the difficulties have become insurmountable. Currently, the debate is about what model will arise after the death of the traditional CD bought at stores. Ominously, several books have been written lately about the death of Classical Music.

In sum, the bad news is that the outlook is not bright and should improve only in the long run. The good news is that, except for the outstanding 1960s and 1970s, things have always been tough. Nevertheless, I think the ground is fertile for the appearance of new “poets” who will again change the panorama of the guitar. But for this to happen, in my opinion certain things need to happen:

- The original repertoire must continue to expand: Although the guitar repertoire is currently more extense and varied than it was thirty years ago, we continue to play the same pieces with irritating frequency. We have to keep expanding the repertoire’s frontiers and encouraging new composers to write new music for the instrument. It is worthwhile to recall that this was the solution for the piano and the violin 200 years ago: Chopin, Lizst, and Paganini, for example, wrote pieces for themselves to play, thus creating a repertoire for themselves and for others. Actually, I think the solution could be precisely this: other guitarist-composers will follow the example of Brouwer and will start to write more quality pieces.

- Focus on the quality of the repertoire, without concessions: We must always strive for maximum quality in the repertoire and flee from the temptation of simplistic trends. There is no use in playing works of unknown fifth-rate composers just to be “different.” Although it is not the ideal situation, it is always better to play a known high-quality piece very well than to try to rescussitate a low-quality piece. Experience tells us that most times these “forgotten” composers (mostly from the 18th and 19th centuries) which are “rediscovered” are merely personal marketing ploys. With rate exceptions, these composers were relegated to oblivion for good reason, and it is better for everyone (artists and the public) that they do remain forgotten. Unfortunately, I still see exceptional guitarists today waste time with such pieces. It is truly a shame. A waste of talent, effort, and time.

- Transcriptions, only when they sound better on the guitar: It is really a shame to see that we still waste precious time trying to play extremely difficult transcriptions of pieces eminently made for the piano, such as sonatas by Mozart or pieces of Ernesto Nazareth. My respects to the guitarists (many of them greater instrumentalists) who continue to try to perform these nearly impossible transcriptions, but in this regard Segovia was wise: why transcribe something that sounds better on the original instrument? Why waste precious time on a simple sonata by Mozart that an average pianist can play effortlessly and that on the guitar will always sound “heavy”? We have to break free from a certain inferiority complex, where it seems that we will only feel like respected artists if we are able to play something by the great classical composers. The transcription of Chaconne “stuck” because it sounds good or better on the guitar than on the violin. Same goes for Albeniz and Granados on the guitar in relation to the piano. As for monumental transcriptions of orchestral pieces by Mussorgsky, Dvorak etc., we must be aware that this is seen by our musician colleagues as a big game of poor taste, almost something of a circus. Transcriptions should be meant to enrich the guitar repertoire, not make a joke of it.

- Small orchestra vs. grand piano: As with almost everything in life, people always prefer the original. The issue is simple: if you’re going to hear a guitar playing as if it were a grand piano, people will prefer the real thing (the piano). Why waste time with a copy in poor taste? What attracts people to the guitar is the delicateness, velvety sound, color, timbre, vibrato, that is, all the aspects of a string instrument. The guitar is the only string instrument that requires the player to keep both hands in direct contact with the instrument and does not need any assistance to produce the sound. The piano not only has a hammer that hits the string, but also has pedals that help sustain or muffle the sound. The violin and the violoncello have the bow, and even the harp has pedals. Since we have to produce all the sound “without help,” then why not use the instruments to produce many different sounds, instead of monotonously playing the same type of sound all the time? Exploring the small orchestra that lives within each guitar is one of the most gratifying things about being a guitarist. We cannot put this opportunity aside. Let’s leave the piano to the pianists; our focus must be to explore the richness of the guitar as it is.

- The choice of instrument is a crucial decision: There is no use in trying to find a small orchestra within the guitar if the chosen instrument is made to sound almost like an electric guitar. If the public wants to hear electric guitar, they should go to a rock concert or a jazz bar. In my opinion, we must find instruments that allow a wide range of sound, both horizontally (sweet and metallic) and vertically (strong and loud). The piano was originally known as “pianoforte” precisely because it allowed pianists to play with different nuances in sound and not just the same type, as with the harpsichord. Despite being an unconditional fan of the Hauser style of lutherie (especially Abreu guitars, which have exceptional quality), I acknowledge that some guitarists can obtain fantastic results with different instruments. I myself played a Fleta for many years. But I do not believe in instruments that do not allow a wide range of sound and timbre. A guitar always played in the same manner sounds like a harpsichord or mandolin. Frankly, I don’t know which is worse.

- Let’s think more like musicians and not just like guitarists: Here is a special message to the poets: more than just guitarists, we are musicians! And more than musicians, we are artists, who have chosen the guitar as a means to express our art. We must always seek our more artistic side. We must constantly strive for musical and personal maturity, and we must be prepared to accept that most times this will take an entire life. In my vision, it is this commitment to art that sensitizes the general public. Segovia and Bream were great artists and musicians, while the majority of their contemporaries, with rare exceptions, were just guitarists. Some were exceptional guitarists, it is true, but unfortunately this is the reality. The public worships, venerates, and supports artists, musicians, and musical personalities. Rarely does the general public support instrumentalists without a veritable musicial personality for a long time.

Conclusion: We are at a historic crossroads. There is no use continuing to pursue the formula of the piano. In my opinion, this led to musical regression in the past twenty years and the consequent flight of the general public and return of the guitarists playing for guitarists pattern. It is also useless to try to go back and imitate Segovia’s style of playing. We must tread our own path, which has really been followed since the 1920s by Andrés Segovia and then perfected in the 1960s by Julian Bream. People easily tire of mechanical guitarists with an ugly sound that have nothing original to say. No one wants to keep hearing someone who only knows how to talk fast in the same tone of voice all the time. People want to feel pleasure and become more sensitive when hearing artists, poets, and musicians. The way of the guitar is poetry, beautiful sound, the small orchestra. There is still time to change course.

Born in Brazil in 1964, Marcelo Kayath began studying the guitar at age 13 with Leo Soares and continued with Jodacil Damaceno and Turibio Santos. When only 16 he won the Segovia Prize at the International Villa-Lobos Competition and 2 years later became the only guitarist to win the coveted Young Concert Artists of Brazil Award. In 1984 he won both the 4th Toronto International Guitar Competition and the Paris Councours International de Guitare and the following year embarked on tours (both solo and with orchestra) of Europe and the USA to unanimous critical acclaim. He also attended the Andrés Segovia Master Class at USC in Los Angeles, where he was given special recognition by Andrés Segovia, who acknowledged him as “an already accomplished guitarist and fine musician”. After early retirement from the concert stage, Mr. Kayath finished degrees in Electrical Engineering from the University of Rio de Janeiro. Despite great success in other career paths besides music he still remains active in the guitar world and has recently produced the following article which was originally presented on Brazilian radio. Mr. Kayath was kind enough to translate this into English and offer it to us for publication.

133 comments