Andrea Tacchi - Rue de la Guitare

In 1980, I journeyed to Paris for the first time in my life, for a full week. This was an adventure I undertook to meet the great Parisian luthiers, and generally take in the guitar culture of this thriving city. This initial experience led to my traveling regularly there for many years afterwards. Before I continue with the highlights and some details of these experiences, I must first mention a little of the process required in advance of the journey.

As hard as this is to imagine, 1980 was a time when the internet was not yet available. Unlike today, it wasn’t possible to sit in front of a computer screen at home, click a few buttons and instantly have the simulated experience of entering into workshops of luthiers all around the world, watch videos and replay just the sections which are of the most interest. Knowledge at that time was not easy to come by.

The first thing I had to do was write letters (in French, of course) to the luthiers I wished to visit, including some photographs of my work as a way to introduce myself, courteously requesting to essentially disturb them with an appointment to meet at an exact day and time. Punctuality was mandatory – even for a young Italian! By agreeing to meet, the maestros would be losing hours to this “curious pest.” Those with whom I met had the graciousness and understanding to know that they were sharing their knowledge and art. These are gifts which should not be hidden otherwise they wither like a plant that gets no water.

Next, I had to get there. Travel was done by train and required spending the night in a sleeping car couchette (which was costly), only to arrive the next day to a strange city where a different language was being spoken, where foreign architecture surrounded me in a different climate with an unfamiliar scent in the air and of course different food! On later trips, I had the good fortune of meeting with a friend from home that perhaps was studying guitar there and would join me in the visits to the various maestros I wished to see. To sum all this up – everything had to coincide, schedules needed to be worked out, and at points the planning could get tiring, but in the end it was just fantastic.

Paris, 1980

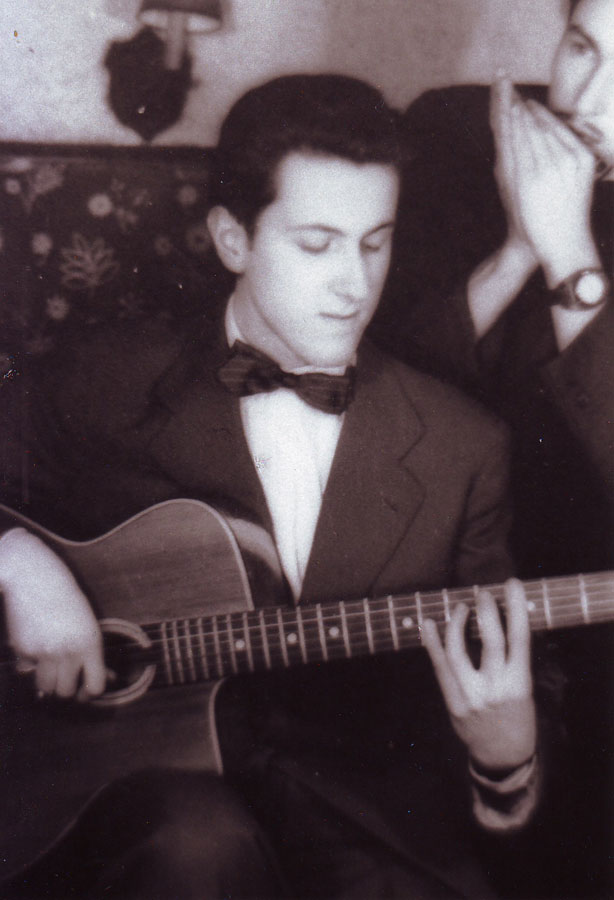

In 1980, I was 24 years old and very curious to visit Paris, since in the Italian guitar world, the French capital had become a place of great allure and mystique. Many of the most talented young Italian guitarists, having barely graduated, moved to Paris to study with Alberto Ponce at the École Normale. This highly specialized school has produced many of the best European guitarists, especially of the generation who are now around 50-60 years old.

Going to Paris was not only about the École Normale however. It was also the place where the prestigious “Radio France” prize was won every year. This prize was the brainchild of Robert Vidal, who as a broadcaster had his weekly national radio program showcasing all aspects of the classical guitar. There was also always great activity in the concert halls, a constant flurry of musical events occurring seemingly without end. There was Isabel Gomez the “Splendid Spanish Queen” who ran a guitar shop called “La Guitarreria” located at Rue d’Edimbourg – this was a place where you could regularly find Robert Bouchet discussing guitars with other patrons. Isabel was helped by her thoughtful assistant, the Japanese guitarist Minoru Inagaki. The shop was located a few steps away from Rue de Madrid, the headquarters of the Paris Conservatory, where Alexandre Lagoya (the companion in life and in music of the legendary Ida Presti) was teaching.

This bustling urban environment attracted a large number of young guitarists, and created a very strong bohemian spirit that energized all who were there. Everywhere people spoke about guitars; there was always a concert the next evening, a contest, an audition. You would regularly find yourself drinking a beer with Roberto Aussel, Alvaro Pierri, or Betho Davezac. Or perhaps you could bump into Maestro Bruno Marlat showing and describing a rare historic Spanish guitar, analyzing its smallest details. For me, it was an inspired place and time for the guitar.

Dominique Field

The first time I met Dominique Field, it was late at night after a concert at Radio France and we were waiting at a bus stop. On the bus it was incredibly noisy and I could hardly understand a word he said, but I liked Dominique very much. We became friends right away. Life was very difficult for us both, as always with young people trying to make their way in the world. During that period I met many young French luthiers, many of whom had to give it up because they could not afford to make a living at it, but Dominique had the persistence of will that it took to succeed. He was an anxious type – he spoke quickly yet was at the same time witty, very kind, always ready with a clever remark, and he is still like that. For me he has been a great friend, of unequalled sincerity and generosity. As I regularly started to visit Paris once or twice every year, I would always be sure to visit with Dominique. When we see each other, we do nothing other than talk and talk of our experiences in our workshops and in life. Our many hours of discussions were filled with agreements on certain things and disagreements on others, yet we always learned a great deal through these exchanges since at its heart was the shared mutual love and interest we both have for the guitar.

Robert Bouchet

It was also in 1980 that I first met Robert Bouchet. After a brief telephone conversation he greeted me in his little house, which was located near his studio on Rue des Ordener. His appearance and mannerisms were very aristocratic – he wore a wool jacket and an ascot around his neck. For some reason on that first encounter I vividly recall seeing a large painting in green and black tones leaning against a wall, turned upside down, it was of a woman ironing clothing on a summer afternoon. My attention quickly turned to the bottle of wine that I had brought as I could tell the maestro wanted to taste it right away. And when he did, in the manner of a sommelier, he commented only with the words “Very Italian”.

It was also in 1980 that I first met Robert Bouchet. After a brief telephone conversation he greeted me in his little house, which was located near his studio on Rue des Ordener. His appearance and mannerisms were very aristocratic – he wore a wool jacket and an ascot around his neck. For some reason on that first encounter I vividly recall seeing a large painting in green and black tones leaning against a wall, turned upside down, it was of a woman ironing clothing on a summer afternoon. My attention quickly turned to the bottle of wine that I had brought as I could tell the maestro wanted to taste it right away. And when he did, in the manner of a sommelier, he commented only with the words “Very Italian”.

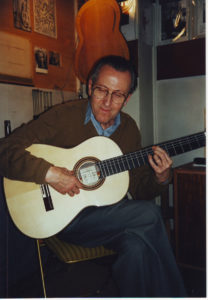

When the moment arrived for me to show him one of my instruments that I had brought along, he was kind with his comments and courteous in his manner of offering suggestions. Then he began to pull his instruments out of some cases that he kept in the sitting room. He showed me his first guitar – his “opus 1,” which was a very simple instrument. He described how he had made the top out of floorboard, and why he built it in the first place: Bouchet was originally a guitar player – a student and aficionado at heart. He had a wartime story that involved his losing his practice guitar with which he had been studying, creating the necessity to replace it with a new one. This prompted the construction of his first guitar. Maestro Bouchet played well, slowly and with sweetness, his aim being to make the timbre of the instrument shine forth. Even in the way he played the guitar, it was obvious that his “visual” approach as an artist was operating somehow through sound – in judging the various dynamic levels, spaces, proportions, pitches, and in the relationship between sound and colors. In the end, sound and aesthetics were for Bouchet, necessarily combined in the totality of the instrument.

I remember among all the guitars he showed me, one guitar was so beautiful that it reminded me of one of those images of a sunburst with rays shooting out on all sides. I believe it was the “Fromage” guitar, so-called by him because he had covered its case with labels for Camembert cheese in imitation of those travelers who, as was the style at the time, attached stickers to their suitcases of hotels and tourist sights of the various cities they’d visited.

Next he took me to visit his workshop on the upper floor of this little apartment, which was part of a huge brick building, with an oversized sign on its façade reading: “Montmartre aux artistes.” This building had been constructed by the city of Paris for its artists. The tiny space he occupied was divided between the bedroom and the workshop, which had originally been a painter’s studio. In Spain and Italy I had already seen a variety of luthier’s workshops, but this was different – it was a kind of appendage belonging to Maestro Bouchet in his total character. Everything was arranged somewhat like a painter’s palette, from which he could easily draw from resources and materials to create his guitars. I was fascinated by the care and imagination with which he had chosen everything that was there – an abundance of containers, phials, and little cigar or bonbon boxes filled with various pieces of wood, capos, and mosaic chips. The many hand tools built by him were made from different woods, always selected for their unique aesthetic characteristics. Even in Bouchet’s tools there was never any detail, be it even a screw or a button that did not receive attention for its ‘visual’ properties that went beyond the merely functional. I looked at his world (which in a similar way I had seen in the old house of the Fleta family on Calle de Los Angeles in Barcelona), much like a child upon entering Santa’s workshop finding his elves at work.

Next he took me to visit his workshop on the upper floor of this little apartment, which was part of a huge brick building, with an oversized sign on its façade reading: “Montmartre aux artistes.” This building had been constructed by the city of Paris for its artists. The tiny space he occupied was divided between the bedroom and the workshop, which had originally been a painter’s studio. In Spain and Italy I had already seen a variety of luthier’s workshops, but this was different – it was a kind of appendage belonging to Maestro Bouchet in his total character. Everything was arranged somewhat like a painter’s palette, from which he could easily draw from resources and materials to create his guitars. I was fascinated by the care and imagination with which he had chosen everything that was there – an abundance of containers, phials, and little cigar or bonbon boxes filled with various pieces of wood, capos, and mosaic chips. The many hand tools built by him were made from different woods, always selected for their unique aesthetic characteristics. Even in Bouchet’s tools there was never any detail, be it even a screw or a button that did not receive attention for its ‘visual’ properties that went beyond the merely functional. I looked at his world (which in a similar way I had seen in the old house of the Fleta family on Calle de Los Angeles in Barcelona), much like a child upon entering Santa’s workshop finding his elves at work.

For me, it was a breathtakingly emotional experience – in front of me there was a man who patiently put together small pieces of wood with glue for hours without end, following only his thoughts and instincts according to his taste, all for the purpose of modeling the materials not to achieve “a sound” but rather “his sound.”

For me, it was a breathtakingly emotional experience – in front of me there was a man who patiently put together small pieces of wood with glue for hours without end, following only his thoughts and instincts according to his taste, all for the purpose of modeling the materials not to achieve “a sound” but rather “his sound.”

After the death of my first unforgettable maestro, Ricardo Branè in 1982, my visits to Paris increased until when, a few years later, Mr. Bouchet also passed away. I had the occasion, after his death, to receive a copy of his handwritten “Cahier D’atelier.” This manuscript was originally given to Dominique Field from Mrs. Bouchet. Field later gave it to the Paris Conservatory and it was eventually copied and published as a beautiful book, with rich commentary provided by Daniel Friederich. As I began to study those notes, I also reflected deeply on the many conversations we had together, and the insights he had shared with me. Those notes became a true obsession and object of study for me until I made the first true copy of a Bouchet guitar in 1995. But the most important lesson he taught me, repeatedly, was that guitars could be made either as objects, or as expressions of one’s temperament, taste, and sense of life. One can make art at the same time as building an instrument. Indeed, one must.

Daniel Friederich

It was during one of these trips that I met with the guitarist Vera Ogrizovic, the daughter of a Yugoslavian diplomat who was stationed in Paris. I knew Vera, as she played one of my guitars, and she was a student of Raphael Andia, professor at the École Normale. It was she who kindly introduced me to the great maestro, Daniel Friederich. For me this was one of the most important introductions of my life; and in my early development as a guitar maker, perhaps no other one person was so singularly influential on my direction in lutherie as Maestro Friederich. And I’d like to specify why – it’s not just because of his fabulous work, but I mean him – the person.

Friedrich is a person of mythical proportions for his intelligence, his dedication to his work, perfection, discipline and perfect work ethic. I was a young man absolutely determined to be a luthier, but I still had a lot to learn. Maestro Friederich treated me with great courtesy and the composure of a true gentleman as he observed my guitar for the first time. He gave me some advice, but at the same time, kept his distance. He did well to do so, seeing as I had a lot to learn, see, and do for myself. I needed to learn the language with which we could communicate.

Mr. Friederich was the son, grandson and descendent of a family of fine wood workers of the highest level, himself a student of an important Parisian school for wood working. He grew up in the historic district of Paris where all the carpenters worked. The art of joinery, planing, the mastery of how to do things well – he had all this in his DNA. Since then I’ve gone back many times to visit. Each time I’ve learned something new and wonderful from him. When, in the 1990’s, Mr. Friederich accepted my proposal to give an interview for “Il Fronimo” (an Italian magazine that he admired), our relationship really changed. It was a complex job that took a long time and several trips to Paris. In addition to many hours of audio recordings of our conversations, the maestro gave me a lot of handwritten notes and sent numerous letters by mail. In the end we were both happy, I had learned a lot and he felt he had been represented accurately.

Mr. Friederich was the son, grandson and descendent of a family of fine wood workers of the highest level, himself a student of an important Parisian school for wood working. He grew up in the historic district of Paris where all the carpenters worked. The art of joinery, planing, the mastery of how to do things well – he had all this in his DNA. Since then I’ve gone back many times to visit. Each time I’ve learned something new and wonderful from him. When, in the 1990’s, Mr. Friederich accepted my proposal to give an interview for “Il Fronimo” (an Italian magazine that he admired), our relationship really changed. It was a complex job that took a long time and several trips to Paris. In addition to many hours of audio recordings of our conversations, the maestro gave me a lot of handwritten notes and sent numerous letters by mail. In the end we were both happy, I had learned a lot and he felt he had been represented accurately.

A couple of years ago I paid him a visit, and he showed me with great enthusiasm how he had slightly changed some of the colors of his rosette, changing the proportions of the rings, and how this new balance perfectly suited the natural hue of the soundboard. Behind the thick lenses of his glasses, his eyes sparkled with youthful enthusiasm. On one of my visits, the guitarist Tania Chagnot telephoned him, and while he was on the phone he left me alone with one of his partially completed instruments which was at the stage before varnishing – the time at which, if there are any defects, they will be visible. There were no defects, everything was perfect and the guitar was just beautiful.

Be sure to also read Andrea Tacchi’s “Il Fronimo” interview with Daniel Friederich.

4 comments