Jack Silver, Pt. 4: On Julio Martinez Oyanguren

<— Go back to Jack Silver, Pt. 3

By Jack Silver

In this series of vignettes, I will be presenting a panorama of artists whose names have for the most part been totally effaced by the passage of the years, but whose artistry has been fortunately preserved on shellac. I am borrowing the title of this survey from Robert Vidal’s pioneering collection of LPs, “Panorama de la Guitare”, released on Erato in beautiful gatefold editions between 1969 and 1978. Never unavailable on CD, it has happily been recently released in a box set, with wonderful performances by such artists as Turibio Santos, Oscar Caceres, Konrad Ragossnig, Barbara Polasek, Leo Brouwer, Betho Davezac, the duo Pomponio-Zarate, and, significantly, an artist who first recorded in the 78 era, Maria Luisa Anido.

A Panorama of the Guitar in the 78 Era

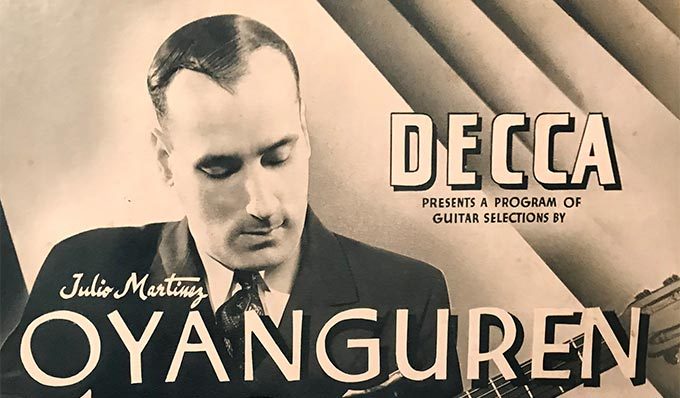

Julio Martinez Oyanguren

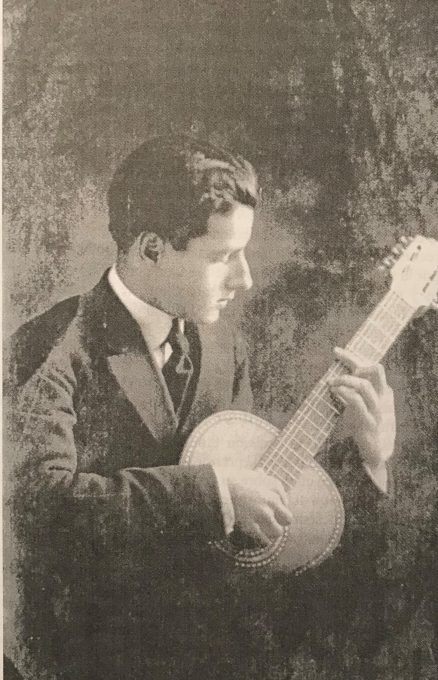

The first contemporary of Andrés Segovia I will highlight is JULIO MARTINEZ OYANGUREN, a Uruguayan virtuoso, who recorded far more than any other guitarist in the 78 era. He is the featured artist on volumes 1 and 8 of Segovia and His Contemporaries, and also appears in volume 11, “Guitarists of the Rio de la Plata”. In fact, I have many more of his recordings in my collection than we have released—three American Decca albums, and individual discs on the Uruguayan label Orfeo. Oyanguren (1901-1973), born in Durazno, Uruguay, studied with Alfredo Hargain, and first performed publically in 1913. When Barrios came to Durazno about that time, Julio was greatly encouraged by the Paraguayan master. They played duets together, and developed a deep friendship that blossomed in the 1920s when both lived in Montevideo. There is a story that Oyanguren had arranged for Barrios to record in New York, but that the Paraguayan master sadly passed away before he was able to make the journey. Had he done so, it is likely that his fame would have spread long before John Williams’ pivotal 1977 recording of Barrios’ compositions. In a concert in 1934 in Durazno, Oyanguren dedicated much of the program to the works of Barrios.

Then, as now, a career as a professional guitarist was fraught with uncertainty, and in 1919 the young Julio enrolled in the naval academy. He continued his musical endeavours, inspired by the blind Spanish guitarist Antonio Jiménez Manjón, who had moved to the Rio de la Plata, and some of whose works he performed. At this time, he was playing a José Ramírez guitar made in 1907 (which is very close in date of make to this 1910 example in GSI’s Museum Archive). He was further stimulated by the concerts of Miguel Llobet, who performed frequently. He graduated in 1924 as an officer and mechanical engineer. He moved to Rome where he continued to study and began composing. Declared “persona non grata” (unwelcome) by Mussolini on account of his liberal convictions, he returned to Uruguay in 1927. His concert career began to blossom in the following years, and he performed widely, including in Brazil.

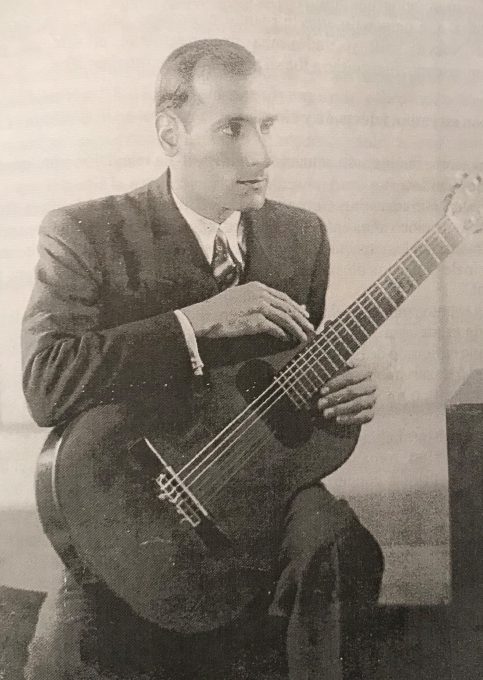

In 1935, he came to the United States with his wife and son. Situating himself and his family in a very dynamic New York, he realized that his South American fame had to be rekindled. His Town Hall debut in October of that year was a tremendous success. He was acclaimed as “the Paderewski of the guitar”, and the doors opened widely for the young artist. He performed with the New York Philharmonic in Lewisohn Stadium in front of an audience of over 18,000, as well as the General Electric Orchestra under Terig Tucci.

Oyanguren had his own weekly radio program on NBC for several years. His student Rolando Valdes Blain remembered turning pages for his teacher as he performed hundreds of works. In 1939, he became the first guitarist to perform at the White House when he performed for Franklin Roosevelt. He later recalled that Roosevelt especially liked the Pericón and Vidalita.

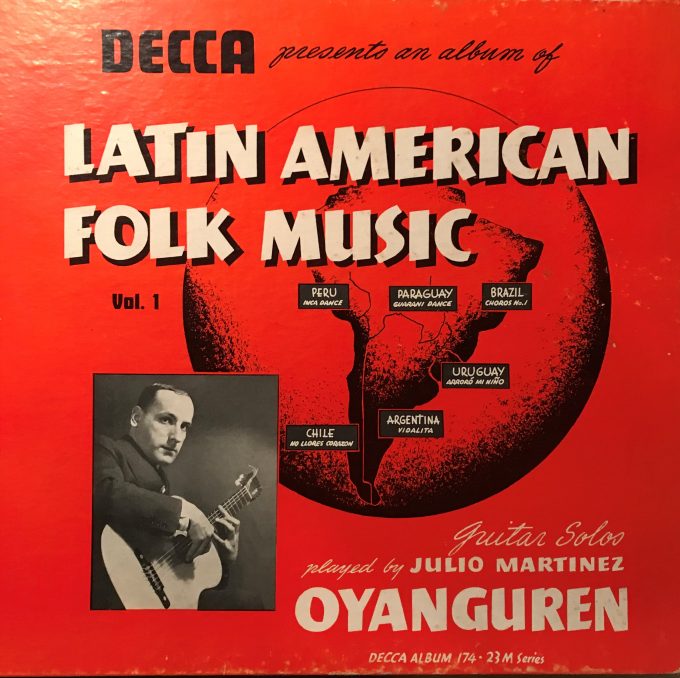

He recorded a wide range of repertoire with RCA, Columbia, and Decca—including, of course, the romantics, foremost among them Tárrega and Albéniz, but also the gamut of his work reached back to the renaissance and baroque—Milan, Narvaez, Sanz, Rameau, Campion, Cimarosa, and to the classical period—Aguado, Ferrandiere, and the first recorded performance of Sor’s “Grand Sonata” and Giuliani’s “Grande Overture”. He recorded contemporary works—Falla’s “Homage à Debussy”, Turina’s “Rafaga”, a Ponce “Cancion”, as well as transcriptions of Brahms, Wieniavski, Massenet, and Schubert. He introduced American audiences to folkloric works from South America, including “La Cumparsita”, “Choros 1” (Villa Lobos), and bambucos, joropos, estilos, Inca dances, gatos and other popular dances. He even waxed some of his own compositions. Oyanguren even provided the musical soundtrack for a film, Gypsy Melody.

Segovia, of course, had been performing in the United States since 1928, and later from 1943 onwards. Indeed, he made his home in New York for twenty years. Naturally, Oyanguren and Segovia were well aware of one another, and there seems to have been an element of competition, even rivalry, between them. A number of stories have circulated over the years, but in the absence of evidence, it is pointless to relate them here. One, relatively amusing, has it that the friendship of the two guitarists dissolved over a disagreement in the fingering of the “Courante” from the fifth Bach Cello Suite. In any case, the press often compared the two, adding fuel to the fire, and Segovia and Oyanguren were often cited, one as the great Spanish guitarist the other as his Latin-American counterpart.

In 1941, Oyanguren decided to return to Uruguay with his wife and three children. Various theories have been suggested to explain this move, but it could have been as simple as a nostalgic longing for his homeland. He came back to Durazno, where he lived for 15 years. He continued to perform widely—on his return he played in Buenos Aires at the Teatro Odeón to rapturous reviews. He toured throughout Uruguay, performed a series of recitals on radio, displaying a repertoire in equal parts classical and folkloric. From 1943 to 1947, he served as the chief of police in Durazno, an unlikely career move for a renowned musician. He subsequently returned to the concert stage. Distinguished composers dedicated works to him: the Brazilian Lorenzo Fernández wrote a “Suite Brasileña” and the Venezuelan Bautista Plaza a “Sonata Antigua”. In 1950, he undertook an extensive tour throughout much of South America.

The year 1956 saw Oyanguren move to Montevideo, where he remained the rest of his life. He continued to perform, compose, and record. Lauro Ayesteran, the eminent Uruguayan musicologist, wrote of Oyanguren that “his name has become part of the history of the guitar, and his prestige, passing beyond critical clamor, has marked him as a guitarist of the highest order.”

2 comments