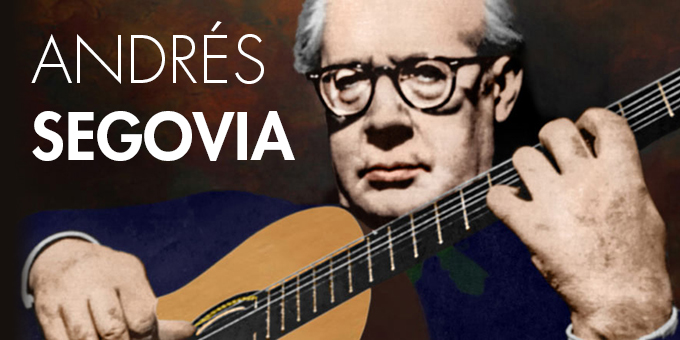

Recording Artist: Andres Segovia

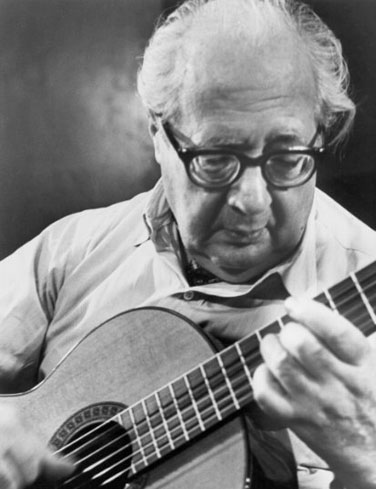

Andrés Segovia (February 21, 1893 – June 2, 1987) was a virtuoso Spanish classical guitarist from Linares, Spain. He has been regarded as one of the greatest guitarists of all time. Many professional classical guitarists today are students of Segovia, or students of his students.

Segovia’s contribution to the modern-romantic repertoire not only included commissions but also his own transcriptions of classical and baroque works. He is remembered for his expressive performances, his wide palette of tone and his distinctive musical personality, phrasing and style.

Segovia was born in Linares, Jaén, Spain. He was sent at a very young age to live with his uncle Eduardo and his wife María. Eduardo arranged for Segovia’s first music lessons with a violin teacher after recognizing that Segovia had an aptitude for music. This proved to be an unhappy introduction to music for the young Segovia because of the teacher’s strict methods, so Eduardo stopped the lessons. His uncle decided to move to Granada to allow Segovia to obtain a better education; after arriving in Granada, Segovia recommenced his musical studies. Segovia was aware of flamenco during his formative years as a musician but stated that he “did not have a taste” for the form and chose instead the works of Fernando Sor, Francisco Tárrega and other classical composers. Tárrega agreed to give the self-taught Segovia some lessons but died before they could meet and Segovia states that his early musical education involved the “double function of professor and pupil in the same body”.

Segovia’s technique differed from that of Tárrega and his followers, such as Emilio Pujol. Both Segovia and Miguel Llobet (who taught Segovia several of his transcriptions of Enrique Granados’ piano works) plucked the strings with a combination of fingernails and fingertips, producing a sharper sound than many of their contemporaries. With this technique, it was possible to create a wider range of timbres, than when using the fingertips or nails alone. Historically, classical guitarists have debated which of these techniques is the best approach. The vast majority of classical guitarists today play with a combination of the fingernails and fingertips.

Segovia’s technique differed from that of Tárrega and his followers, such as Emilio Pujol. Both Segovia and Miguel Llobet (who taught Segovia several of his transcriptions of Enrique Granados’ piano works) plucked the strings with a combination of fingernails and fingertips, producing a sharper sound than many of their contemporaries. With this technique, it was possible to create a wider range of timbres, than when using the fingertips or nails alone. Historically, classical guitarists have debated which of these techniques is the best approach. The vast majority of classical guitarists today play with a combination of the fingernails and fingertips.

Segovia’s first public performance was in Granada in 1909 at the age of 16. A few years later, he played his first professional concert in Madrid, which included works by Tárrega and his own guitar transcriptions of J.S. Bach. Despite the discouragement of his family, who wanted him to become a lawyer, and criticism by some of Tárrega’s pupils for his idiosyncratic technique, he continued to diligently pursue his studies of the guitar.

He played again in Madrid in 1912, at the Paris Conservatory in 1915, in Barcelona in 1916 and made a successful tour of South America in 1919. Segovia’s arrival on the international stage coincided with a time when the guitar’s fortunes as a concert instrument were being revived, largely through the efforts of Llobet. It was in this changing milieu that Segovia, whose strength of personality and artistry coupled with new technological advances such as recording, radio, and air travel, succeeded in making the guitar more popular again.

In 1921 in Paris, Andrés Segovia met Alexandre Tansman, who later wrote a number of guitar works for Segovia, among them “Cavatina”, which won a prize at the Siena International Composition contest in 1952.

In Granada in 1922, Segovia became associated with the Concurso de Cante Jondo promoted by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla. The aim of the “classicizing” Concurso was to preserve flamenco in its purity from being distorted by modern popular music. Segovia had already developed as a fine tocador of flamenco guitar, yet his direction was now classical. Invited to open the Concurso held in Alhambra, Segovia chose to play Homenaje a Debussy by Falla.

In 1923, Segovia traveled to Mexico for the first time. There Manuel Ponce was so impressed with Segovia’s concert that he wrote a review in El Universal. Later Ponce went on to write many works for Segovia, including numerous sonatas.

In 1924, Andrés Segovia visited the German luthier Hermann Hauser Sr. after hearing some of his instruments played in a concert in Munich, and thus the historically legendary relationship was forged between the Spaniard player and the German luthier. In 1928, Hauser provided Segovia with one of his personal guitars for use during his U.S. tour and for use in all his concerts through 1933. In 1928, both Segovia and Llobet visited Hauser. Segovia was impressed by the quality of Hauser’s work and wrote his impressions, noting that he “immediately saw the potential of this great artisan if only his mastery might be turned to the construction of the guitar in the Spanish pattern, as immutably fixed by [Antonio de] Torres and [José] Ramírez as the violin had been fixed by Stradivarius and Guarnerius” (Segovia in Guitar Review 1954). Segovia encouraged Hauser to build instruments based on his 1912 Manuel Ramirez guitar (built by Santos Hernandez) after he examined and made measurements of this instrument. At this time, Hauser also had the opportunity to examine Miguel Llobet’s famous 1859 Torres, which would also become a decisive influence on the maturing “Hauser” style. When Hauser delivered a new instrument that Segovia had ordered, Segovia passed his 1928 Hauser to his U.S. representative and close friend Sophocles Papas, who gave it to his classical guitar student, the famous jazz and classical guitarist Charlie Byrd, who then used it on several records.

In 1924, Andrés Segovia visited the German luthier Hermann Hauser Sr. after hearing some of his instruments played in a concert in Munich, and thus the historically legendary relationship was forged between the Spaniard player and the German luthier. In 1928, Hauser provided Segovia with one of his personal guitars for use during his U.S. tour and for use in all his concerts through 1933. In 1928, both Segovia and Llobet visited Hauser. Segovia was impressed by the quality of Hauser’s work and wrote his impressions, noting that he “immediately saw the potential of this great artisan if only his mastery might be turned to the construction of the guitar in the Spanish pattern, as immutably fixed by [Antonio de] Torres and [José] Ramírez as the violin had been fixed by Stradivarius and Guarnerius” (Segovia in Guitar Review 1954). Segovia encouraged Hauser to build instruments based on his 1912 Manuel Ramirez guitar (built by Santos Hernandez) after he examined and made measurements of this instrument. At this time, Hauser also had the opportunity to examine Miguel Llobet’s famous 1859 Torres, which would also become a decisive influence on the maturing “Hauser” style. When Hauser delivered a new instrument that Segovia had ordered, Segovia passed his 1928 Hauser to his U.S. representative and close friend Sophocles Papas, who gave it to his classical guitar student, the famous jazz and classical guitarist Charlie Byrd, who then used it on several records.

Segovia’s first American tour in 1928 was arranged by Fritz Kreisler, the Viennese violinist who privately played the guitar, when he persuaded F.C. Coppicus from the Metropolitan Musical Bureau to present the guitarist in New York. After Segovia’s debut in the U.S., the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos composed his now well-known Twelve Études (Douze études) and later dedicated them to Segovia. Their relationship proved to be lasting as Villa-Lobos continued to write for Segovia for years. Villa-Lobos also transcribed numerous classical pieces himself and revived the pieces transcribed by predecessors like Tárrega.

In 1932, Segovia met and befriended composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco in Venice. Since Castelnuovo-Tedesco did not play the guitar, Segovia provided him with guitar compositions (Ponce’s Folias variations and Sor’s Mozart Variations) which he could study. Castelnuovo-Tedesco composed a large number of works for the guitar, many of them dedicated to Segovia. The Concerto Op. 99 of 1939 was the first guitar concerto of the 20th century and Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s last work in Italy before he emigrated to the United States. It was premiered by Segovia in Uruguay in 1939. In 1935, Andrés Segovia gave his first public performance of Bach’s Chaconne, a famously difficult piece for any instrument. Around this time, Segovia also moved to Montevideo, performing many concerts in South America during the 1930s and early 1940s.

After World War II, Segovia became among the first to endorse the use of nylon strings instead of gut strings. This new advance allowed for greater stability in intonation, and was the final missing ingredient in the standardization of the classical guitar. Segovia began to record more frequently and perform regular tours in Europe and the U.S., a schedule he would maintain for the next thirty years until about the 1970s. In 1954, Joaquín Rodrigo dedicated “Fantasía para un gentilhombre” (“Fantasy for a Gentleman”) to Segovia. In 1958, the Spanish guitarist won a Grammy Award for Best Classical Performance, Instrumentalist for his recording Segovia Golden Jubilee. John W. Duarte dedicated his English Suite Op.31 to Segovia and his wife (Emilia Magdalena del Corral Sancho) on the occasion of their marriage in 1962. Segovia told Duarte “You will be astonished at the success it will have”.

After World War II, Segovia became among the first to endorse the use of nylon strings instead of gut strings. This new advance allowed for greater stability in intonation, and was the final missing ingredient in the standardization of the classical guitar. Segovia began to record more frequently and perform regular tours in Europe and the U.S., a schedule he would maintain for the next thirty years until about the 1970s. In 1954, Joaquín Rodrigo dedicated “Fantasía para un gentilhombre” (“Fantasy for a Gentleman”) to Segovia. In 1958, the Spanish guitarist won a Grammy Award for Best Classical Performance, Instrumentalist for his recording Segovia Golden Jubilee. John W. Duarte dedicated his English Suite Op.31 to Segovia and his wife (Emilia Magdalena del Corral Sancho) on the occasion of their marriage in 1962. Segovia told Duarte “You will be astonished at the success it will have”.

Segovia was a selective guitarist and only performed works with which he identified personally. He was known to reject atonal works, or works which he considered too radical, even if they were dedicated to him; he had rejected Frank Martin’s Quatre pièces brèves, Darius Milhaud’s Segoviana and others. Even though rejected by the legendary guitarist, these works are all published and available today. Segovia’s repertoire consisted of three principal pillars: firstly, contemporary works, including concertos and sonatas, usually specifically written for Segovia himself by composers he forged working relationships with, notably Spaniards such as Federico Moreno Torroba, Federico Mompou, and Joaquín Rodrigo, the Mexican composer Manuel Ponce, Italian composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, and the great Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. Secondly, his repertoire consisted of transcriptions, usually made by Segovia himself, of classical works originally written for other instruments (e.g., lute, harpsichord, piano, violin, cello) by J.S. Bach, Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, and many other prominent composers. Thirdly, traditional classical guitar works by composers such as Sor and Tárrega. Segovia’s influence enlarged the repertoire, mainly as a commissioner or dedicatee of new works, as a transcriber, and to a far lesser extent as a composer of such works as in his “Estudio sin luz”.

Segovia viewed teaching as vital to his mission of propagating the classical guitar and gave masterclasses throughout his career. His most famous masterclasses took place at Música en Compostela in the northern Spanish city of Santiago de Compostela. His teaching style is a source of controversy among some of his former students, who considered it to be dogmatically authoritarian. One of Segovia’s most celebrated former students of the classical guitar, John Williams, has said that Segovia bullied students into playing only his style, stifling the development of their own styles. Williams has also said that Segovia was dismissive of music that did not have what Segovia considered the right classical origins, such as South American music with popular roots.

Segovia also taught at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena for numerous years, where he was aided by Alirio Díaz. Later it was Oscar Ghiglia who continued the Siena class. In recognition of his contributions to music and the arts, Segovia was ennobled on June 24, 1981 by King Juan Carlos I, who gave Segovia the hereditary title of Marqués de Salobreña (Marquis of Salobreña) in the nobility of Spain.

Andrés Segovia continued performing into his old age, living in semi-retirement during his 70s and 80s on the Costa del Sol. Two films were made of Segovia’s life and work—one when he was 75 and the other when he was 84. They are available on DVD titled Andrés Segovia — in Portrait. His final RCA LP record (ARL1-1602), Reveries, was recorded in Madrid in June 1977.

In 1984, Segovia was the subject of a thirteen part series broadcast on National Public Radio, entitled Segovia! The series was recorded on location in Spain, France, and the United States. Hosted by Oscar Brand, the series was produced by Jim Anderson, Robert Malesky, and Larry Snitzler.

Segovia passed away in Madrid of a heart attack at the age of 94. He is buried at Casa Museo de Linares, in Andalusia.

Segovia influenced a generation of classical guitarists who built on his technique and musical sensibility, including such luminaries as Christopher Parkening, Julian Bream, John Williams and Oscar Ghiglia, all of whom have acknowledged their debt to him. Further, Segovia left behind a large body of edited works and transcriptions for classical guitar, including several transcriptions of J.S. Bach, in particular, an extraordinarily demanding classical guitar transcription of the Chaconne from the 2nd Partita for Violin (BWV 1004). During his lifetime, guitarists were eager to claim association with Segovia, and Segovia himself suggested that he had not actually taught as many students as has been claimed; he once said, “All over the world I have ‘pupils’ I have never met.” His editions of works originally written for guitar include newly fingered and occasionally revised versions of works from the standard repertoire (most famously, his edition of a selection of twenty estudios by Fernando Sor, the “cornerstone” of every serious student’s technique since its publication in 1945, although somewhat ironically Segovia in the preface to that work disparaged Sor as “not among the vigorous talents”) as well as compositions written for him, including by Heitor Villa-Lobos, Federico Mompou, and Castelnuovo-Tedesco. Many of the latter were edited by Segovia, working in collaboration with the composer, before they were first published. Because of Segovia’s predilection for altering the musical content of his editions to reflect his interpretive preferences, many of today’s guitarists prefer to examine the original manuscripts, or newer publications based on the original manuscripts in order to compare them with Segovia’s published versions, so as to accept or reject Segovia’s editorial decisions.

Segovia influenced a generation of classical guitarists who built on his technique and musical sensibility, including such luminaries as Christopher Parkening, Julian Bream, John Williams and Oscar Ghiglia, all of whom have acknowledged their debt to him. Further, Segovia left behind a large body of edited works and transcriptions for classical guitar, including several transcriptions of J.S. Bach, in particular, an extraordinarily demanding classical guitar transcription of the Chaconne from the 2nd Partita for Violin (BWV 1004). During his lifetime, guitarists were eager to claim association with Segovia, and Segovia himself suggested that he had not actually taught as many students as has been claimed; he once said, “All over the world I have ‘pupils’ I have never met.” His editions of works originally written for guitar include newly fingered and occasionally revised versions of works from the standard repertoire (most famously, his edition of a selection of twenty estudios by Fernando Sor, the “cornerstone” of every serious student’s technique since its publication in 1945, although somewhat ironically Segovia in the preface to that work disparaged Sor as “not among the vigorous talents”) as well as compositions written for him, including by Heitor Villa-Lobos, Federico Mompou, and Castelnuovo-Tedesco. Many of the latter were edited by Segovia, working in collaboration with the composer, before they were first published. Because of Segovia’s predilection for altering the musical content of his editions to reflect his interpretive preferences, many of today’s guitarists prefer to examine the original manuscripts, or newer publications based on the original manuscripts in order to compare them with Segovia’s published versions, so as to accept or reject Segovia’s editorial decisions.

Andrés Segovia can be considered a catalytic figure in granting respectability to the guitar as a serious concert instrument capable of evocativeness and depth of interpretation. It was Federico Moreno Torroba who said: “The musical interpreter who fascinates me the most is Andrés Segovia”. He can be credited to have dignified the classical guitar as a legitimate concert instrument before the discerning music public, which had hitherto viewed the guitar merely as a limited, if sonorous, parlor instrument.

0 comment