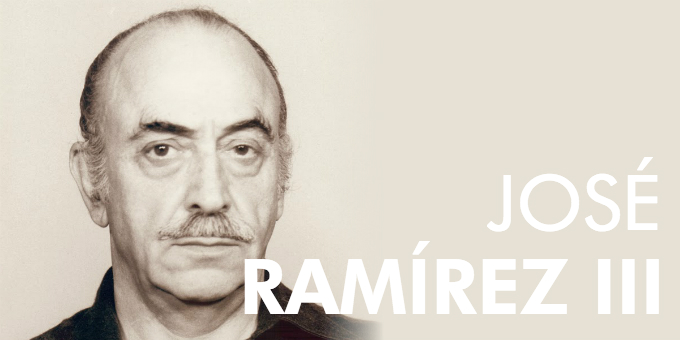

Luthier: Jose Ramirez III

Current Inventory | Past Inventory

José Ramírez III (1922 – 1995) was without doubt one of the most influential and important luthiers in the second part of the 20th century. His guitars influenced hundreds of instrument makers, many of whom imitated him, and thousands of guitarists around who played his instruments. Indirectly, he even influenced composers of the guitar who found for the first time that their music could be heard in large concert halls instead of small chamber music environments. It could be argued that José III had a more profound effect on the development of the modern guitar than any other guitar maker in history.

So what was his secret, and why do we make such sweeping claims about his importance? One paramount reason is that José III was the first and only luthier to be able to standardize the process of making a classical guitar such that it could be built by any well-trained artisan, according to his precise plan and under his supervision. Moreover, the design was such that these instruments, although not made by him personally, stood up to and often exceeded the quality of the best handmade instruments of the day.

José Ramírez III was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1922. His father José II had left Spain for a brief tour of South America after the turn of the century and ended up staying for nearly 20 years. In I923, on the news of the death of his own father, José II moved the family back to Madrid, and it was at this time that he took over his late father’s guitar workshop. At the age of 18, José III began working as an apprentice and within a few years was building guitars and experimenting on his own. In I957, he took over the duties as ‘maestro’ (master) of the Ramírez workshop, which by now had spanned three generations, and he continued to develop what would become the Ramírez concert guitar that we know today. This instrument was typified by its large body, long string length, and cedar or spruce top. It had great power, as well as sustain, sweetness, a fullness of tone and a balance across the entire register. José III died in 1995 at the age of 73.

José Ramírez III was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1922. His father José II had left Spain for a brief tour of South America after the turn of the century and ended up staying for nearly 20 years. In I923, on the news of the death of his own father, José II moved the family back to Madrid, and it was at this time that he took over his late father’s guitar workshop. At the age of 18, José III began working as an apprentice and within a few years was building guitars and experimenting on his own. In I957, he took over the duties as ‘maestro’ (master) of the Ramírez workshop, which by now had spanned three generations, and he continued to develop what would become the Ramírez concert guitar that we know today. This instrument was typified by its large body, long string length, and cedar or spruce top. It had great power, as well as sustain, sweetness, a fullness of tone and a balance across the entire register. José III died in 1995 at the age of 73.

Probably his most enduring contribution was his role as a teacher and as a developer of talent. We often measure a man’s greatness not only by what he achieves in his lifetime, but by what he leaves behind for others to complete, and by how he influences those in his wake. From the 1960s to the 1990s, the José Ramírez workshop had assembled and trained many of the most talented guitarreros of José III’s generation, many of whom continue to work on their own with great individual success. This collection of greatness under one roof has only been approached by that of Manuel Ramírez (José III’s great-uncle) or his grandfather, José Ramírez I, whose workshops collectively included the likes of Santos Hernández, Enrique Garcia, Domingo Esteso, Emilio Pasqual Viudes, Modesto Borreguero, Julian Goméz Ramírez and many others.

José III’s roster, however, is still unmatched when you consider the number of great luthiers who began their careers there. They include Paulino Bernabé, Manuel Contreras, Mariano Tezanos, Enrique Borreguero Marcos, Pedro Contreras Valbuena, Manuel González Contreras, Miguel Malo Martínez and so on.

“I make sure that everything is done exactly as I want it,” José III told George Clinton in 1984. “The architect doesn’t have to get involved with the bricklaying. My pupils learn from me so they know exactly what is to be done, otherwise I would do it myself. The wood and the tools have no secrets from me, and if there are problems I have to sort them out.”

Quantity is not always a virtue, especially in art or the work of artisans. However, in the case of José III, his guitars became the standard for musicians worldwide because he was able to produce roughly 20,000 concert instruments during the course of his lifetime, which was somewhere between 20 and 40 times that of his average competitor. Not only did José III succeed in seducing the majority of concert artists of his day to play Ramírez guitars, but he provided instruments to their students, as well as to several generations of the amateurs who followed them.

The second reason for Ramírez pre-eminence as master guitar maker was his capacity for innovation. He experimented with the use of western red cedar from North America as a tonewood for the soundboard, and eventually popularized it as the alternative to northern European spruce, which had been the standard for virtually all stringed instruments including pianos, violins and lutes.

“We had some old instruments made of a sort of red-coloured spruce and with a very straight grain,” José III told Clinton. “It was impossible to obtain this sort of wood, but you might have come near to it with some very old furniture… Well, one day I sent one of my young fellows to buy wood and when he returned he said the supplier had what he thought was Honduras cedar. I told him to go back and bring a sample. When he returned I saw immediately that the wood had the characteristics I had always been looking for. I went myself and bought a large piece of trunk, took it to the workshop, and cut a top from it. I gave it to one of my craftsmen and told him to build a top from it. When the guitar was finished we realized at once that although this wood required a different working, it was not only good but superior. At first I was criticized for using it, but little by little more makers realized its worth and changed to it.”

This use of cedar was one of the most important and significant developments in the history of the modern guitar. If anyone doubts this, consider that this wood has become the preferred soundboard material for the instruments of the majority of guitar-playing concert artists, including Pepe Romero, John Williams, Christopher Parkening and Manuel Barrueco, to name a few. It also became the preferred wood for tops among several of the world’s most acclaimed luthiers, such as Ignacio Fleta, Daniel Friederich and Miguel Rodríguez Jr. Another remarkable and central innovation occurred in the 1960s when, most probably at the request or influence of Andrés Segovia, José III began to introduce the long string length of 664 mm in his guitars. This gave the instrument more power to project in a large concert hall and also accommodated the huge hands of the maestro. Although it has in recent years fallen out of favor, this increased string length became the standard among guitar makers and guitarists throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and is still preferred today by many performers who need to fill large concert halls, or those who are lucky enough to find themselves playing with an orchestra.

All of José III’s innovations led to his building of one particular model, the “1A Tradicional” we know today, amongst improvements to other models. Many world-renowned players were immediately drawn to this new guitar, among them Andrés Segovia, who began his career with a guitar made by Manuel Ramírez. After opting for a German instrument (Hermann Hauser) for many years, in the 1960s Segovia decided to return to a Spanish instrument. Partly because of nationalistic sentiment, but also due to the need for a guitar with enough volume to fill a large concert hall, he played on José Ramírez guitars to the end of his days. Thus one of the greatest careers in the history of the classical guitar began and ended with Ramírez guitars.

José III did not, of course, arrive at his designs through chance, and has experimented widely. “I’ve tried everything,” he told Clinton. “Double top; double back; I know all about Lacôte and his experiments with double tops… Look inside the guitar! We are just doing what 90 percent of guitar makers have done before. Everybody has a look at the secrets.” He also realized early in his career that some people appeared to miss what seems self-evident: the primary aim should be to achieve a fine-sounding instrument. “When I couldn’t achieve this I was very upset, and then I determined to study the guitar hard. I soon realized that the guitar was a very detailed work and that I needed more knowledge about the physics and the science. There might be a little art in making the rosette and putting the guitar together, but the sound is purely a product of physics. I know I’m not doing myself any favors in saying this, because I would like to be thought of as an artist. But it is so.”

José III did not, of course, arrive at his designs through chance, and has experimented widely. “I’ve tried everything,” he told Clinton. “Double top; double back; I know all about Lacôte and his experiments with double tops… Look inside the guitar! We are just doing what 90 percent of guitar makers have done before. Everybody has a look at the secrets.” He also realized early in his career that some people appeared to miss what seems self-evident: the primary aim should be to achieve a fine-sounding instrument. “When I couldn’t achieve this I was very upset, and then I determined to study the guitar hard. I soon realized that the guitar was a very detailed work and that I needed more knowledge about the physics and the science. There might be a little art in making the rosette and putting the guitar together, but the sound is purely a product of physics. I know I’m not doing myself any favors in saying this, because I would like to be thought of as an artist. But it is so.”

José Ramírez III was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1922. His father José II had left Spain for a brief tour of South America after the turn of the century and ended up staying for nearly 20 years. In I923, on the news of the death of his own father, José II moved the family back to Madrid, and it was at this time that he took over his late father’s guitar workshop. At the age of 18, José III began working as an apprentice and within a few years was building guitars and experimenting on his own. In I957, he took over the duties as ‘maestro’ (master) of the Ramírez workshop, which by now had spanned three generations, and he continued to develop what would become the Ramírez concert guitar that we know today. This instrument was typified by its large body, long string length, and cedar or spruce top. It had great power, as well as sustain, sweetness, a fullness of tone and a balance across the entire register. José III died in 1995 at the age of 73.

Probably his most enduring contribution was his role as a teacher and as a developer of talent. We often measure a man’s greatness not only by what he achieves in his lifetime, but by what he leaves behind for others to complete, and by how he influences those in his wake. From the 1960s to the 1990s, the José Ramírez workshop had assembled and trained many of the most talented guitarreros of José III’s generation, many of whom continue to work on their own with great individual success. This collection of greatness under one roof has only been approached by that of Manuel Ramírez (José III’s great-uncle) or his grandfather, José Ramírez I, whose workshops collectively included the likes of Santos Hernández, Enrique Garcia, Domingo Esteso, Emilio Pasqual Viudes, Modesto Borreguero, Julian Goméz Ramírez and many others.

José III’s roster, however, is still unmatched when you consider the number of great luthiers who began their careers there. They include Paulino Bernabé, Manuel Contreras, Mariano Tezanos, Enrique Borreguero Marcos, Pedro Contreras Valbuena, Manuel González Contreras, Miguel Malo Martínez and so on.

Finally, although there has been much said about José III over the years, it cannot be denied that the guitar which he designed in the early 1960s still stands as the world standard of the concert classical guitar, a standard by which all other guitars are measured and will be measured in years to come.

– Tim Miklaucic

From The Classical Guitar: A Complete History, published by Balafon Books, 1997

read THE JOSÉ RAMÍREZ DYNASTY

0 comment